IF YOU HAVEN’T READ Ian Fleming’s Thrilling Cities, I reckon you probably should if you like witty, readable books. At least have a glance at a witty, readable review of it. One key passage that could do with some elaboration is this one:

Fleming was periodically weighed down by a kind of directionless, spiteful ennui, which often fired his best writing – Casino Royale, From Russia, with Love, “The Living Daylights”, “Octopussy”. Reading his novels in sequence, one is bewildered by the mood swings between, for instance, From Russia, with Love, the cynical book in which Fleming comes closest to Le Carré, and actually kills 007 at the end (obviously, it didn’t stick), and its follow-up, the dizzyingly exuberant Doctor No. Today, he’d probably be called bipolar.

It’s unsurprising, really, that Fleming in a foul mood should kill off 007. It wasn’t only his general attitude toward life that was affected by his mood swings, but also his attitude towards his most famous creation. Gleefully pulpy Bond adventures such as Live and Let Die, Moonraker, Doctor No, Goldfinger and Thunderball burst with such genretastic staples as pirate gold, disguised Nazi war criminals, Chinese evil geniuses, all-lesbian crime gangs and missing atomic weaponry. Fleming grew up reading about the exploits of John Buchan’s Richard Hannay, Sapper Morton’s Bulldog Drummond, and Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu, and at his most carefree seemed delighted to be keeping alive that lineage.

At other times, he was rather more cynical about his place in the literary world and seemed, as with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes, to view his creation as an albatross keeping him from achieving greater literary respect.

Of course, Fleming did have some heavyweight admirers in the literary world. Kingsley Amis was the most prominent, writing two books of analysis of the character, one serious and one tongue in cheek, as well as a continuation novel after Fleming’s death. Roald Dahl, too, counted himself as a fan and wrote the screen treatment for You Only Live Twice. Raymond Chandler thought Fleming a fine thriller-writer, and he should know. Anthony Burgess noted that he had read and enjoyed every one of the Bond novels.

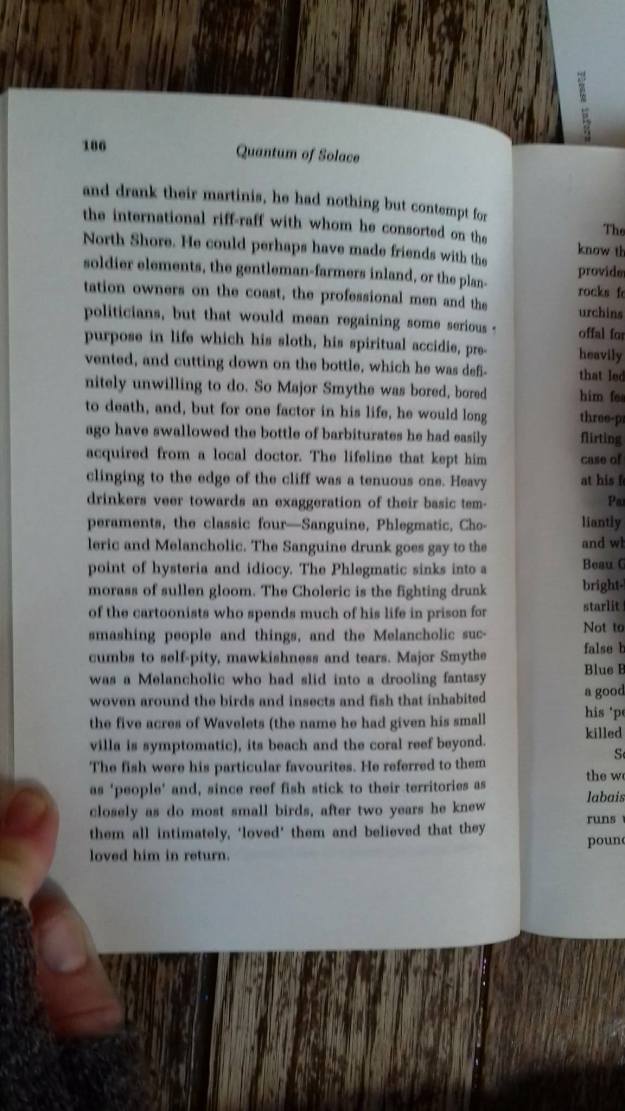

What Fleming lacked, though, was any body of work outside of Bond on which to be judged, with the small exceptions of the children’s book Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and two nonfiction books: the aforementioned Thrilling Cities and The Diamond Smugglers, cobbled together from leftover research for Diamonds Are Forever. That’s not to say that the Bond books are entirely without literary merit; just view the passage below from “Octopussy” for evidence:

-it’s just that the obvious limitations of the Bond format of exotic locales, dastardly villains, daring escapades, and sex and booze and food and sex and cigarettes and sex and death don’t much reward experimentation, which is likely why most of Fleming’s occasional stabs at literary fiction are in the short-story format. “Octopussy”, excerpted above, is a slow and rather melancholy rumination on guilt and probably the peak of Fleming’s ability as a writer.

In the same collection appeared “The Living Daylights”, which returns us to somewhat more familiar territory with Bond ordered to snipe a Soviet sniper in order to aid a defection. We’re thoroughly in Le Carré territory here, and treated to such stylistic flourishes as Bond’s mental description of Berlin as “a glum, inimical city dry varnished on the Western side with a brittle veneer of gimcrack polish, rather like the chromium trim on American motor-cars”.

Earlier, Fleming had taken Bond as far away from formula as he’d ever get with “Quantum of Solace”, a stylistic and thematic homage to Somerset Maugham with Bond appearing only to listen to another character whose party he’s attending tell him a story about two other figures and their broken marriage. It’s good stuff if a little pastichey, with the only really unconvincing element being the questionable necessity of having Bond himself appear at all.

Mind you, the Bond of the short-stories spent about as much time relaxing as he did going on missions. “The Hildebrand Rarity” introduces us to a truly vile American businessman, Milton Krest, and his vessel the Wavekrest. Krest has no plan more dastardly than to use somewhat unethical fishing techniques to retrieve the rare fish of the title, but he’s a more convincing portrait of evil than a whole cartoonish parade of Draxes, Goldfingers and Blofelds. We finally end up in murder-mystery territory as Krest is found murdered with two possible suspects (we as readers are allowed to know James Bond didn’t do it) and a subversive lack of solution.

Finally, there’s one Bond novel that attempts to enter literary-fiction territory (though look out for flourishes in Casino Royale and From Russia, with Love): The Spy Who Loved Me, in which a nice yet somewhat broken Canadian girl recounts her life and sexual history for two-thirds of the novel before Bond shows up and takes care of the thugs menacing her in the present. It was released to reviews ranging from indifferent to hostile, and Fleming quickly decided he was embarassed by it, leading to a film “adaptation” that used the novel’s title and very little else. Actually it’s really not that bad (aside from one cringeworthy line extolling the merits of “semi-rape”) if one’s able to accept that it’s really not much of a Bond adventure.

Still, its reception seems to have put Fleming off from doing anything other than sticking to what he knew best, and he stuck to formula for the superb On Her Majesty’s Secret Service before the rushed You Only Live Twice and The Man with the Golden Gun. One wonders how he would have fared in the literary world had he not been so afraid to experiment; the presence of Bond himself in each of these stories feels like nothing more than a crutch and they’d all be the better off simply ditching the whole pretence. But I suppose albatrosses aren’t easily got rid of.